The Soft Power of Pad Thai: Lessons for Building Filipino Food in America

You may have seen the headlines lately—debates about America retreating from its role as a cultural and diplomatic leader, pulling back from foreign aid, public diplomacy, and even global institutions. There’s been criticism of “wokeness,” skepticism toward cultural exports, and a rising chorus of isolationist sentiment.

But here’s the thing: America’s growth, reach, and even dominance have never been driven by military might alone. What truly built American influence was its soft power—its music, media, universities, brands, ideals, and yes, its food. Think blue jeans, jazz, McDonald’s, Marvel, and Sesame Street. These weren’t just exports. They were invitations. And they built a global network of goodwill that shaped international policy, business, and belief.

So when we talk about soft power, we’re not just talking about flavor—we’re talking about strategy. And when countries invest in it, they’re opening the aperture on how they want to be seen, respected, and remembered.

What Is Soft Power?

Soft power can take many forms—education, culture, music, film, tourism, food. And in many spiritual traditions—Christianity included—we call this “breaking bread”.

I’ve been a student of food for as long as I can remember. Maybe it started with that first box of Whitman’s chocolates my dad brought back after a long deployment. Or maybe it was the guacamole my mom made me bring to my fourth-grade teacher, Mr. Ramirez—a proud Mexican man who was tough as nails. I still remember the way he looked at me: eyebrows raised, a puzzled smile forming, and then—"Wow. Nikki, That’s good”.

That’s the thing about food. It disarms. It softens. It opens people up. One bite, and suddenly you’re seen—not just for what you made, but for where you come from. And if you can be seen, you can be remembered. That’s soft power in its simplest form.

So when I think about how food can shift narratives and shape global reputations, I don’t just think about branding or Michelin stars. I think about strategy. I think about storytelling. And I think about Thailand.

Rewriting the Narrative

Because before Thai food was beloved, it was misunderstood. Before it was available in every Trader Joe’s, it was almost nowhere. And before Thailand became a travel darling celebrated for its food and exquisite beaches, it was better known—especially in the West—for its sex tourism industry, a reputation shaped in part by decades of media and the Vietnam War’s R&R culture.

But Thailand didn’t settle for that story. It rewrote it.

It launched a strategic, state-sponsored rebrand—one that used food as the cultural front door. And it worked.

Now consider this: there are only about 340,000 Thai people in the United States—and yet their cuisine is everywhere. Compare that to the 4.4 million Filipino Americans, and the fact that we make up less than 1% of U.S. restaurants.

The idea of saying, “Pad Thai or sushi for dinner?” would’ve once been unthinkable. Thai food wasn’t an American staple. Not yet.

The Global Thai Program

So how did it happen?

In 2002, Thailand launched what would become one of the most successful gastrodiplomacy campaigns in modern history: the Global Thai Program. But the groundwork started years earlier, in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. Thailand needed to repair its reputation, diversify its exports, and strengthen its global influence. Food, they realized, could do all three.

The Thai government designed three restaurant models—fast-casual, midscale, and upscale—each with business plans, menus, and interior design blueprints. They offered low-interest loans through national banks and issued chef manuals to ensure consistency abroad. They trained chefs. They partnered with embassies. They certified authenticity through the Thai SELECT program.

It wasn’t just a food campaign. It was national branding with flavor.

Resistance, Results, and Reputation

There were skeptics, of course. Thai restaurateurs in the U.S. worried about government interference. Some chefs questioned the standardized menus. But momentum won out. By 2011, the number of Thai restaurants worldwide had doubled to over 10,000. Dishes like green curry, papaya salad, and tom yum became part of the global vernacular.

Thai food began showing up in suburbs, airport terminals, college towns. Imports of Thai jasmine rice, chili paste, and fish sauce skyrocketed. And alongside the cuisine came curiosity—about the country, the culture, the people. Tourism surged. Thailand was no longer just a destination. It became a global brand.

A Playbook for the Philippines

This is what gastrodiplomacy looks like when it’s done with intention. And it’s what inspires me as I continue building a future for Filipino cuisine—one that is grounded in identity but designed for scale. Because if Thailand could do it with 340,000 Thai Americans… imagine what we could do with 4.4 million.

But we’ll need a strategy. Not just pride. A plan. Not just passion. And yes—some soft power. Served hot.

Key Takeaways:

Soft power is not a luxury—it’s a national strategy that builds trust, appeal, and cultural presence.

Thailand used gastrodiplomacy to rewrite a global narrative and become a top-tier culinary and tourist destination.

They created scalable restaurant models, invested in chef training, standardized menus, and offered government support.

Thai food’s global ubiquity is the result of intentional, state-backed efforts—not accident or hype.

With 4.4 million Filipinos in the U.S., the opportunity for Filipino food is enormous—but it requires more than pride; it needs coordination, mentorship, and entrepreneurship.

Lessons for Building Filipino Food

I get asked a lot—a lot a lot—"Nicole, what are your thoughts on Filipino food today?"

And I have to say: I push back—hard—on the idea that we’re at the apex of our success. Especially if you're Filipino or into Filipino food, your social media algorithm is probably feeding you the latest wins, the chefs to follow, the features in glossy magazines. And don’t get me wrong—I love it. I celebrate it. But let’s not confuse visibility with victory.

We still have work to do. And most of that work lies in entrepreneurship.

Because without business infrastructure—without places to try, fail, build, and scale—we stay stagnant. For decades, many Filipinos leaned into professions that promised security: medicine, nursing, engineering, academia. Professions that offered a 401(k), a pathway, a plan. That made sense. That still makes sense.

But if we want Filipino food to grow—to really take its seat at the table—we have to mentor, support, and fund the next generation of chefs, makers, and founders. We need test kitchens and investors. Incubators and educators. Access to ingredients. Access to capital. Access to each other.

We need to not just dream it—but do it.

That’s the next chapter.

And we get to write it—together.

Curiously,

Nicole

All photos Jeepney, 1-800-Lucky, Nicole Ponseca

Choriburger

Sisig

Valeria Moraga

Key elements included:

Three Restaurant Models:

Elephant Jump (fast-casual: $5–15/person)

Cool Basil (midscale: $15–25/person)

Golden Leaf (upscale: $25–30/person with Thai-inspired interiors)

Standardized Playbooks: Menus, interior design guides, and branding templates were provided to help entrepreneurs set up shop abroad.

Financial Support: $15 million USD in early funding. Thai banks offered loans up to $3M for overseas restaurants.

Chef Training: Government-published chef manuals and culinary schools trained Thai chefs to maintain consistency abroad.

Thai SELECT Certification: Created by the Ministry of Commerce to verify authentic Thai restaurants overseas.

Embassy Coordination: Thai embassies hosted food festivals, chef demonstrations, and matchmaking between restaurateurs and global markets.

Key Players

Ministry of Commerce – Department of Export Promotion led execution

Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Embassies acted as promotional arms

Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra – Launched the Global Thai Program

Prime Minister Chuan Leekpai – Initiated soft power groundwork post-1997

Queen Sirikit – Elevated Thai culture and cuisine as a diplomatic tool

Foreign Minister Kantathi Suphamongkhon – Publicly championed food as policy

Chef David Thompson – Michelin-starred Nahm, brought global credibility

Chef McDang (Sirichalerm Svasti) – Culinary ambassador and educator

Chef Chumpol Jangprai – Co-founder of R-Haan, now 2 Michelin stars

Lessons for Filipino Cuisine

Intentional nation branding matters

Food can change how the world sees you—but only if you define the message. If not, someone else will.Taste isn’t enough. Infrastructure is everything

Thailand didn’t rely on flavor alone. It built supply chains, training, design guides, and certifications to ensure scale.Government and private sector must collaborate

When embassies, entrepreneurs, and institutions act in harmony, the impact compounds.You don’t need millions. You need momentum

There are only 340,000 Thai Americans. There are over 4.4 million of us. Thai food scaled because it had a blueprint. Filipino food can, too.

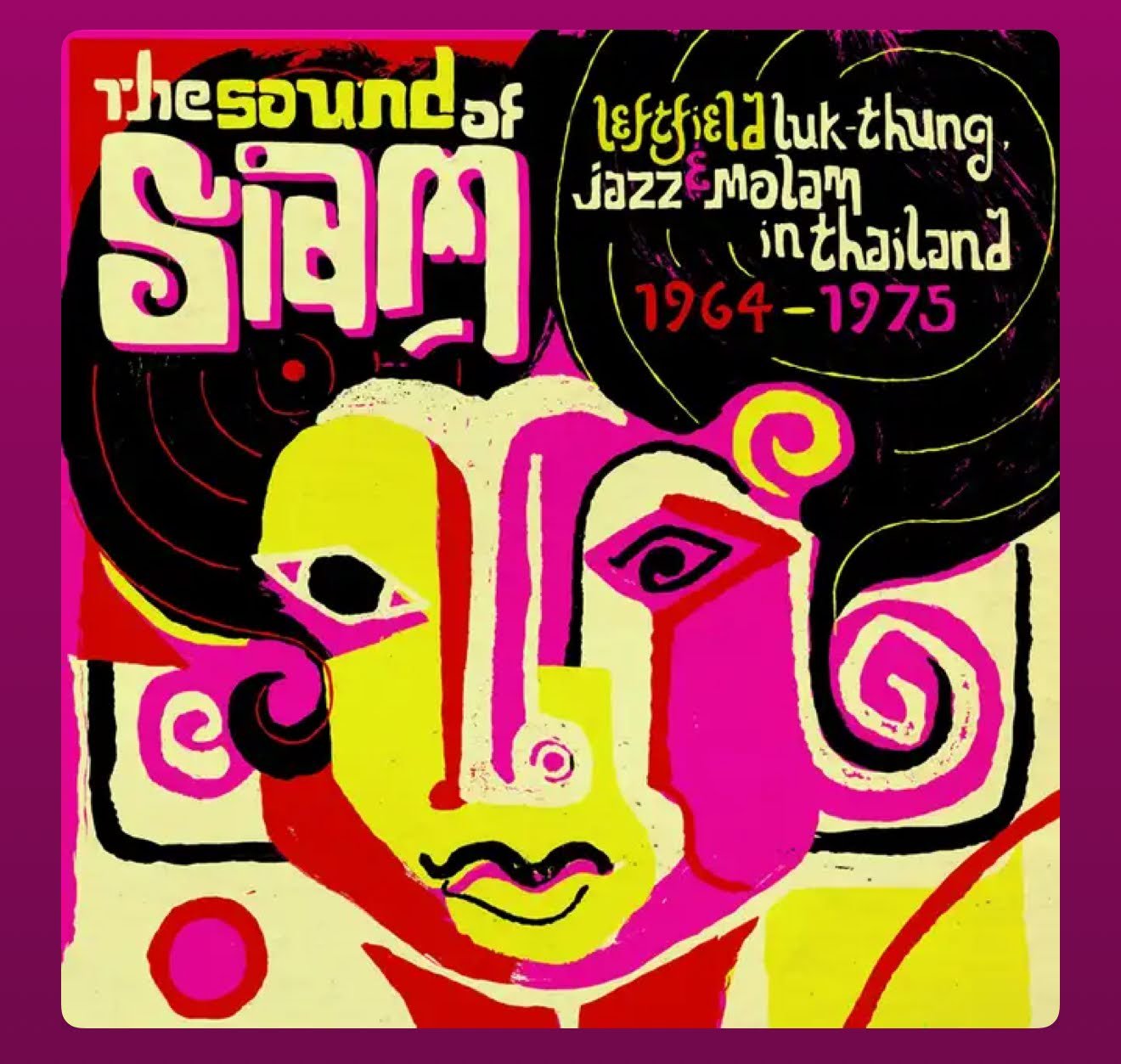

Soundtrack for this Week

Sound of Siam

Tagalog Word of the Day:

SILOG

Silog is a Filipino portmanteau combining "sinangag" (garlic fried rice) and "itlog" (egg), commonly used to describe popular Filipino breakfast dishes that feature garlic rice, a fried egg, and a main protein. The name of the dish changes depending on the meat served—for example, tapsilog (with tapa), longsilog (with longganisa), or tosilog (with tocino).

Pagising ko kanina, naamoy ko agad ang longsilog na niluluto ni Mama—sinangag, itlog, at longganisang Iloko na paborito ko talaga.

"When I woke up earlier, I immediately smelled the longsilog Mama was cooking—garlic rice, egg, and Ilocano-style sausage, which is my favorite."

May 4, 2025

Newsletter #50